'I Hate Math!' – How I Turned My Daughter's Math Hatred Into Quiet Confidence

When my daughter screamed 'I hate math!' and refused to do homework, I made every wrong response. Here's what finally worked after months of battles, tears, and one surprising discovery.

The words hit me like a slap. 'I HATE MATH! I'm not doing it and you can't make me!' My eight-year-old daughter Lily slammed her homework folder shut and burst into tears. This wasn't the first time. It wasn't even the tenth time. But something about the raw desperation in her voice that evening made me realize: we had a serious problem. And worse—I'd been handling it completely wrong for months. What followed was a six-month journey of trial and error, research, failure, and finally—breakthrough. If your child is telling you they hate math, I hope our story helps you avoid the mistakes I made.

How It Started

Lily loved kindergarten math. Counting bears, sorting shapes, playing number games—she'd come home excited to show me what she'd learned. First grade was mostly fine too. But somewhere in second grade, things shifted. The worksheets got harder. The timed tests started. And slowly, that spark in her eyes when she talked about numbers... disappeared.

The Night Everything Changed

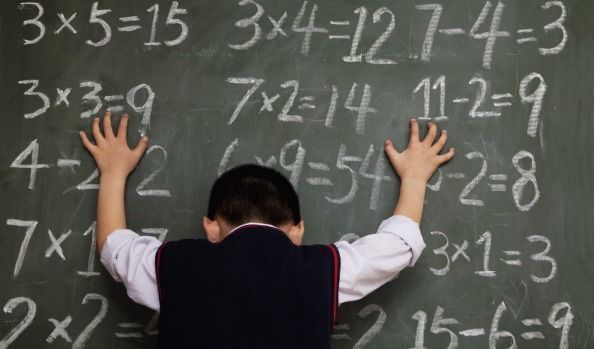

By third grade, homework had become a nightly battle. That particular evening, she'd been staring at 20 multiplication problems for an hour. She'd completed three. When I gently reminded her that dinner was almost ready, that's when it erupted: 'I HATE MATH!' followed by the folder slam and the tears. I'd heard 'I hate math' before. But this was different. This was genuine anguish.

Every Wrong Response I Made

Looking back, I cringe at how I responded in those early months. I tried every instinctive response—and every single one made things worse.

'No You Don't!'

My first instinct was to correct her. 'You don't hate math, you're just frustrated.' Result: She'd argue harder, proving how much she really did hate it. I was invalidating her feelings, and she knew it.

'Math Is Important!'

I'd launch into explanations about how she'd need math for jobs, money, cooking, everything. Result: Her eyes would glaze over. Lectures about future importance mean nothing to an eight-year-old in distress right now.

'You're Good at Math!'

I tried reassurance. 'But you got an A on your last test! You're good at this!' Result: She'd look at me like I was crazy. Her experience told her she wasn't good at it—who was I to contradict her reality?

'I Hated Math Too'

I thought commiserating would help. 'I know, honey. I hated math when I was your age too.' Result: I was basically giving her permission to continue hating it. If Mom hated math and turned out fine, why should she push through?

'Just Try Harder'

This was the worst. 'If you'd just focus and try harder, you'd get it.' Result: Tears, shutdown, and the unspoken message that her struggle meant she wasn't trying. She was trying. Harder than I realized.

Every one of these responses—correction, lectures, false reassurance, commiseration, pressure—pushed Lily further away from math, not closer.

Understanding What 'I Hate Math' Really Means

After weeks of nightly battles, I started researching. What I learned changed my entire approach. When children say 'I hate math,' they're usually expressing something deeper:

- •'I feel frustrated and I don't know how to express it'

- •'This makes me feel stupid, and I hate feeling stupid'

- •'I'm embarrassed that other kids seem to get it and I don't'

- •'Math makes me anxious and my brain shuts down'

- •'I don't understand why I should care about this'

- •'I'm tired and overwhelmed and math is the breaking point'

It's emotional, not logical. And here's the key insight that changed everything for me: emotions need validation before they can change. You can't argue someone out of a feeling.

The Turning Point

One evening, instead of responding with my usual playbook, I tried something different. Lily said 'I hate math,' and I just... sat with it. 'It sounds like math is really frustrating you right now,' I said quietly. She paused. Looked at me. And then, instead of arguing or crying, she said: 'Yeah. It is.' That was it. That tiny moment of feeling heard opened a door that had been slammed shut for months.

What Started Working

Validation First, Always

I learned to acknowledge her feelings before trying to fix anything. 'That does sound hard.' 'I can see you're really frustrated.' 'It makes sense that you feel that way.' No arguing. No minimizing. Just recognition that her experience was real.

Curiosity Over Correction

Instead of telling her how to feel, I started asking questions. 'What part feels hardest right now?' 'Did something happen at school today?' 'When you think about math, what comes up?' The answers surprised me. It wasn't all of math she hated—it was timed multiplication tests. That specific thing triggered all her anxiety.

Breaking the Monolith

'Math' is huge and abstract. We started breaking it into pieces. 'Maybe not all math—which part is hardest right now?' Turned out she actually liked geometry and patterns. It was calculation under pressure that she hated. Suddenly we had something to work with.

Normalizing Struggle

I started saying things like: 'A lot of people find math frustrating sometimes. Even mathematicians get stuck.' 'Your brain is learning something new—it's supposed to feel hard.' 'Struggling doesn't mean you're bad at it. It means you're growing.' She needed to know she wasn't broken.

Leaving the Door Open

Instead of trying to convert her to math-love immediately, I planted seeds. 'Your feelings about math might change. Lots of people end up liking it when something clicks.' No pressure to change now. Just possibility for later.

The Soroban Discovery

About three months into our new approach, I stumbled across the Japanese abacus—the soroban—while looking for alternatives to worksheets. I was skeptical at first. How would wooden beads help a child who hated math? But something about it being different, being physical, being not-a-worksheet intrigued me.

Why It Worked for Lily

The soroban worked for three reasons I didn't expect. First, it was novel—not associated with her math trauma. Second, it was physical—she could touch, move, manipulate. Third, there were no timers, no grades, no comparison to classmates. It was just her and the beads.

The first time she got a calculation right on the soroban, she looked up with genuine surprise. 'That was... kind of fun,' she said cautiously, like she was admitting something forbidden. I didn't make a big deal of it. 'Yeah?' I said. 'Want to try another?' She did.

The Slow Shift

Change didn't happen overnight. For weeks, the soroban was just 'that bead thing'—tolerated, not loved. But slowly, something shifted. She started asking to practice without being prompted. She'd show her little brother how to count on it. One day I overheard her telling a friend, 'I'm learning Japanese math. It's actually pretty cool.'

The goal was never to make her love math overnight. It was to make her relationship with math tolerable enough that she'd give it another chance. The soroban provided that bridge.

Practical Strategies That Made a Difference

- •Shorter sessions: 10 minutes of willing practice beats 45 minutes of battle

- •Choice: 'Do you want to use the soroban or play a math game?' gives control

- •Connecting to interests: Lily loves baking, so we did recipe math together

- •Modeling struggle: I'd do puzzles in front of her and say 'This is hard!' without quitting

- •Celebrating effort: 'You stuck with that even when it was frustrating. That takes guts.'

Working With Her Teacher

I also had an honest conversation with Lily's teacher. 'She's really struggling emotionally with math,' I explained. 'Is there anything we can do to reduce the pressure while we work on building her confidence?' Her teacher was more understanding than I expected. She reduced Lily's homework load and let her skip the timed tests temporarily while we rebuilt her foundation.

The Words That Changed

About four months in, Lily said something that made me stop in my tracks. She was working on her soroban when she said, quietly: 'I don't hate math anymore, Mom. I just... don't love it yet.' Don't love it YET. That tiny word meant everything. She'd gone from absolute hatred to possibility. That was huge.

Where We Are Now

Today, Lily is ten. She still wouldn't call math her favorite subject—that's reading, by a mile. But she no longer dreads it. She can do mental calculations that surprise her classmates. She even volunteered to help a younger student who was struggling with addition. 'I used to hate math too,' I heard her tell him. 'But then I found a different way to learn it.'

For Parents in the Battle Phase

If you're currently living through nightly math battles, I want you to know: it can get better. Not instantly. Not without effort. But it can change. Here's what I wish someone had told me at the beginning:

- •Your child's hatred is a symptom, not the problem. Address the underlying cause.

- •Validation is not agreement. You can acknowledge their feelings without accepting defeat.

- •The goal is tolerance, not love. A functional relationship with math is enough.

- •Different approaches work for different kids. If worksheets aren't working, try something else.

- •Your own math attitude matters. If you model stress about math, they'll absorb it.

What I'd Tell My Past Self

If I could go back to that night when Lily slammed her folder and screamed that she hated math, I'd tell myself: stop trying to fix it immediately. Sit with her. Let her feel heard. Then, when the storm passes, get curious about what's really going on. And for the love of everything, put the flashcards away.

The Long View

Math education isn't a sprint. Your child doesn't need to love math by Friday. They need to develop enough competence and confidence to use math as a tool throughout their life. That takes time. It takes patience. And sometimes, it takes finding a completely different approach than what's being taught at school.

Your Child's Math Story Isn't Over

Whatever your child is feeling about math right now—the hatred, the tears, the avoidance—it's a chapter, not the ending. With patience, the right tools, and a shift in how we respond to their frustration, the next chapter can be completely different. Lily's was. Yours can be too.

Ready to try a different approach to math? Sorokid's soroban-based learning feels nothing like homework—which is exactly why it works for children who've developed math resistance.

Start Free Trial